By Eepa

When many people think of living outdoors, they think of Camping. Camping, backpacking, and hiking are recreational activities that are an enjoyable way to experience nature during those rare moments of free time. These activities can incorporate elements of bushcraft/fieldcraft, but these activities have very different expectations for required gear, periods of time expected to be afield without resupply, and security considerations.

In this primer on living in the wilderness, we will discuss the needs of people who are living on the land as they move to safer territory and the needs of people who will be living remotely long term as a bugout or as a function of being involved in a resistance struggle. This will include the basic elements of fieldcraft for a revolutionary: water, shelter, fire, food, and navigation.

Water

Water is what will get ya. A lack of it will leave you disoriented, tired, and dead. Unclean water will get you sick, potentially killing you, or will just taste disgusting, limiting your intake, leading to dehydration. Clean, palatable water is the first priority of any person seeking to live off grid. As a someone utilizing field craft to survive, it is advised that you maintain a redundancy of methods to get safe drinking water. We will examine three easy methods to take with you when you venture into the woods in a bugout situation.

Steel Water Bottle

The first think you should carry is a steel water bottle. Make sure the bottle doesn’t have any plastic on the main body and make sure it is single walled (not insulated double walled). This will allow you to carry water with you and will allow you to boil water to sanitize it. Boiling water for 1 minute is sufficient to clean it according to the WHO. Make sure it is a rolling boil with consistent, fast bubbling. That’s when you start the clock for the 1 minute time.

Boiling water only sanitizes it, it does not purify it. By covering the end of the bottle with a bandana and securing it to the mouth with a hair-tie or rubber band, you can filter out a lot of sediment, making the water taste significantly less gritty. This the most time consuming way to get clean water. You need to drink the remainder of your water, filter fresh water into the bottle, start a fire, get the bottle to a boil, let cool. This is a fail safe, but there are faster ways to get clean water when you are on the move. See the video below by the press filter, for a water boiling demonstration.

Tablets & Chlorine Bleach

Tried and tested, you can use water purification tablets or a small amount of unscented plain household chlorine Bleach. This option again benefits from pre filtering the water through a bandana. It will leave a taste, something that dedicated water purification tablets try to correct as much as possible. There will still be a taste with tablets.

Bleach can be purchased in bulk and stored in dropper bottles, making dispensing correct amounts easier. This is by far the cheapest and easiest to acquire method of purifying water. Here is a guide from the EPA on amounts of bleach to use with a given volume of water:

| Volume of Water | Amount of 6% Bleach to Add* | Amount of 8.25% Bleach to Add* |

|---|---|---|

| 1 quart/liter | 2 drops | 2 drops |

| 1 gallon | 8 drops | 6 drops |

| 2 gallons | 16 drops (1/4 tsp) | 12 drops (1/8 teaspoon) |

| 4 gallons | 1/3 teaspoon | 1/4 teaspoon |

| 8 gallons | 2/3 teaspoon | 1/2 teaspoon |

Tablets come in a wide variety of forms. One of my favorites is the two step Potable Aqua Water Purification Tablets (iodine based purification), with included PA Plus, a neutralizing agent that reduces the flavor of the initial purification tablets. These come is small bottles of 50 tablets that will treat a 32 oz bottle of water 25 times. Chlorine tablets are also available, though the taste has led me to have less experience with these tablets. One special note about Iodine tablets, they will stain soft water bladders, so take that into consideration.

When treating the water in your bottle, it is important to very slightly loosen the lid of the bottle after mixing, and allow some of the water with the purification chemical to flow past the threads on the mount and lid of your bottle. Failure to do this will leave untreated water on the mouth and lid, potentially infecting you. The colder it is, the longer you will need to keep the tablets in the water before drinking (cold water reduces the efficiency of the purification chemicals). Instructions will remind you of these factors.

An alternative to these is a UV light water purification lamp. These are stirred in water while illuminated, killing harmful microbes. These have a major downside; they need batteries. If you have a solar charger integrated into your system, this is a good option. Otherwise, you will be caring a lot of heavy batteries for extended use.

Water Filters

Water filters are the top of the line when it comes to getting clean, tasty water. Filters require that water be forced through various filtering elements in order to produce clean, drinkable water.

Squeeze Filters

One of the most basic is a water bottle adaptor like the Sawyer Squeeze. The benefit to this is that you can drink from any bottle with standard water bottle threads (like a SmartWater or Aquafina). You do have to squeeze while drinking, which wears out bottles.

Pump Filters

Pump type filters are excellent for their ability to fill multiple containers fast. They require a lot of pumping, which can be taxing if you are trying to conserve calories in a long term bugout or bushcrafting situation. The MSR Guardian is the top choice in the pump filter category for its durability and self cleaning features. These are best for small groups as their size and weight is a bit much for an individual.

Gravity Filters

Gravity filters are excellent choices for static or semi-static camps with multiple people. Water is purified by hanging a bag and letting gravity pull the water through the filter. This can be done overnight and topped of throughout the day, providing a ready source of water for refills. The Katadyn Base Camp, the LifeStraw Mission, and the Platypus GravityWorks are good options for this role. These are best for small groups as their time to filter can be long, but they do filter larger volumes of water without much supervision or effort.

You can also build gravity filters for long term survival in the wilderness. Here is a good video demonstrating a self made gravity filter:

Press Filter

One of the best options for a personal use either in a bugout bag or for individual patrol is the Grayl Geopress. This all in one filter acts as both the filter and the bottle. Instead of pumping or squeezing, this bottle works by filling the bottle with water, inserting the filter, and pushing down with your body weight. This is a super efficient means of filtering water requiring very few calories of effort. You can press once to fill your steel bottle, then press again to fill the Geopress. That gives you a days worth of water extremely fast, silently, and with no trace. The filters are good for ~115 days of use with 3 uses per day. If you are filtering extremely dirty water, this may be reduced. If you are planning on being out for more than 100 days, carry a spare filter. Here’s a video explaining how to source your water for the geopress:

Shelter

Shelter is what you use to insulate yourself from the elements; from the cold, from the heat, from the sun, from the wind. Typically this is used while sleeping, but it also might be useful when doing tasks around camp. The needs of fieldcraft shelters are different than the needs for camping. In fieldcraft, we need our shelters to provide three things: durability, ease of deployment/takedown, and concealment. These factors will change based on the environment so we will examine three options that can be used in the situations you might find yourself.

Tarp

Tarps are the most basic form of shelter. They provide shade, protection from precipitation, and some protection from wind. Tarps can be made into a variety of shelters using surrounding trees or trekking poles as supports. Tarps can also be used to protect you from precipitation in the form of a bed roll or poncho and can be used to create a gurney in an emergency. Tarps also serve a useful role in serving as a waterproof/water resistant barrier for more semi-permanent bush shelters.

Essentially, tarps are some of the most useful objects you can have to fit a variety of situations. Important factors to look for when selecting a tarp is material, seems, and grommets.

Nylon ripstop is the way to go for tarps as it resists tearing and offers good water proofing naturally. 40D Nylon is good when you are really concerned about weight, but for long term field craft, 70D will be much more durable. Seems should be heat taped or sealed to prevent leaks. Grommets and loops should be reinforced to prevent tear-out.

The top recommendation for a good, durable tarp would be AquaQuest. Their defender series (2.4-3.3lbs) is pretty bullet proof but their guide series (0.9-1.2lbs) will work well if weight/bulk is a concern. 10×7 is good for an individual, but 10×10 expands your tarp use options and allows for up to two people sleeping, four to six sitting.

Concealment is a factor here, so depending on your environment choose an appropriate color. Remember, plain olive drab green looks more like a typical backpacker and might raise less suspicions than a camo tarp. OD green is very good at blending with backgrounds at a distance. These can be quickly taken down, even in an emergency abandonment of camp by cutting the ridge line, pulling ground spikes and stuffing it into your backpack.

There are dozens of ways to set up a tarp shelter. Try some different styles when camping and build an understanding of which styles work best for your needs.

Bivy

Bivies are… intimate. They are designed to hold you and your sleeping bag, maybe with the sleeping pad inside and maybe outside. They are quick to set up, provide adequate protection, and are extremely low profile. You want to buy quality materials here, usually gore-tex, and you want to make sure that there is adequate ventilation to vent the moisture from your breath, especially if you have to zip up in inclement weather. A hoop to keep the bivy off of your face is really a creature comfort worth looking for. Bivies are incredibly good at blending in given proper site location. For urban/suburban travel in bad weather, the bivy is a good option to consider. Do your research and practice using it a lot in your local climate. I have had good experiences with the Dutch army surplus bivy, but the camo patter would stick out in urban environments.

Tent

Tents can be the most secure form of shelter you can have in a field craft situation. They resist wind and precipitation better than any form of rapidly moveable shelter out there. The type recommended for fieldcraft use is the pyramid tent. Pyramid tents com in three to twelve sided pyramids, with their unique feature being support via a single center pole. They are extremely quick to set up. Four stakes into the corners, then erect the pole inside. Done. These are very stable in wind and handle precipitation well. They are also easy to get dressed in and can protect yourself and your gear in all conditions.

The Luxe Outdoors Minipeak Pyramid Tent (2.18lbs) is a great pyramid tent that allows for mosquito netted inner tent (either one or two person).

A lightweight and rugged option (though expensive) is the Mountain Laurel Designs Duomid (1.1lbs). Built with strong silnylon or DCF, these tents are the gold standard for pyramid tents. Upgrading to an interior mosquito net is expensive.

Other tents will work, but the flat panels of a pyramid tent are easy to mend should they require it and a broken center pole can be easily replaced with a staff from a sapling or with crossed poles outside of the tent. Other tent designs, like the ones that use crossed flexible fiberglass poles, will fail under high winds, leaving you with a tent bowing down against you and transferring water onto you in the night. The more seems a tent has, the more points of failure you will have to watch. Backpacking tents are also are much slower to take down and stow should you need to evacuate camp in an emergency.

Bushcraft Shelters for Weather & Extended Stay

Bushcraft shelters are different than camping shelters in that they use materials gathered from nature to build the shelter. Bushcraft shelters offer better insulation from wind, rain, snow than tents or tarps alone, though they require more calories and time to make. If you plan on being static for a period of time, one of these shelters can serve you well. Be aware that there is a flood of trendy ‘bushcraft shelter’ construction videos that are questionable at best and downright dangerous at worst. Learn to make these shelters from books and respected outdoor survival instructors.

The most basic form of bushcraft shelter is the basic lean-to. A good lean-to built against a rock face or facing a fire can provide substantial protection from snow and winds. Learn this type of shelter first along with how to make bedding, then develop your skills from there.

Fire

Starting fire reliably is incredibly important. Unlike recreational camping or backpacking, we do not want to rely on fuel resupply to provide us with heat. This means starting a fire from scratch. As with water, we want to pack with redundancy in mind, to make sure we can start a fire no matter what happens. Usually this means having three fire starters and two sources of tinder.

Fire Starters

There are many kinds of fire starters out there, some of which you can construct in the field if you have a knife. We will look at carry along fire starters you can pack with you and practice with now, focusing on the recommended fire starters for fieldcraft. There are other options; feel free to try them as well. These are just the ones I am recommending.

Windproof Lighter or Matches

When looking for lighters, the first thing that comes to mind is the ubiquitous Bic lighter. These are butane lighters that burn for a long time and are reliable, unless they get cold or are exposed to wind. The UCO Stormproof or SM torch butane lighter are a good go-to option for lighters as they ignite butane in a high temperature torch that resists wind better. Keep lighters against your body in an inner pocket to keep them warm and ready for use.

Matches are fickle, but stormproof matches will work in all kinds of weather and will work even after being submerged in water. Stormproof matches also have longer guaranteed burn time, meaning you have longer to ignite your tinder and kindling to get your fire started. In practical use, I have found the UCO Titan Stormproof Matches, with their 25 second burn time, to be an excellent fire starter. There are other makers out there, so feel free to try some and find a match maker you like.

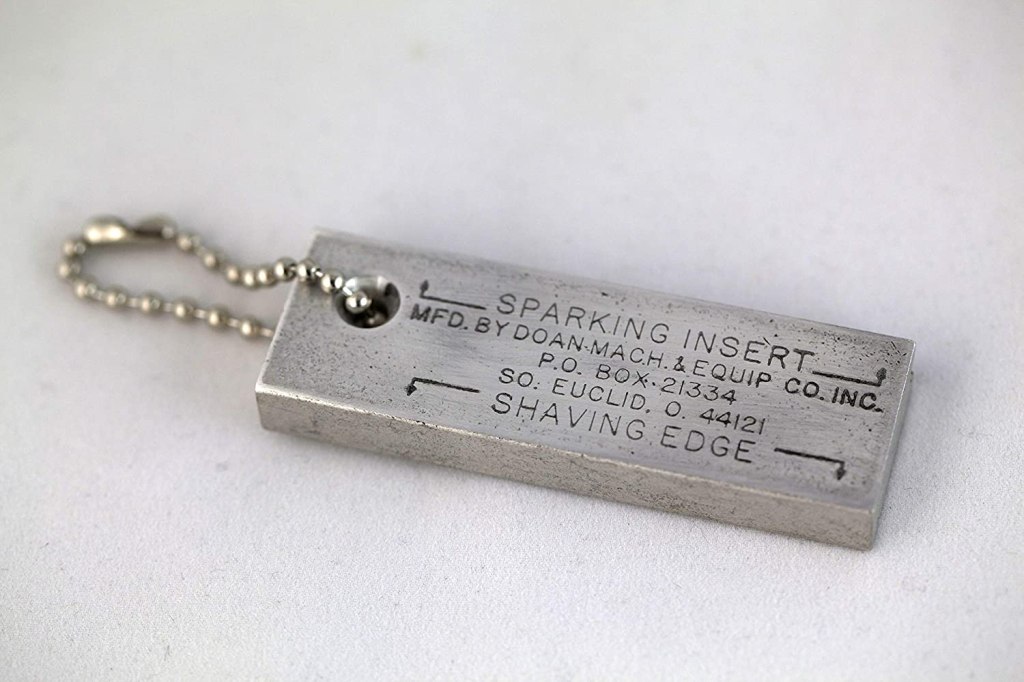

Ferro Rods

Ferro rods produce a shower of sparks when the spine of a knife or axe is pushed along their surface (the right knives can be found here). They produce extremely hot sparks (5,500°F/3,000°C) and are excellent for igniting dry tinder. Most of the ferro rods you see sold with survival kits or as knife accessories are incredibly small. Get a ferro rod that is 6-8″ in length for a good long strike, and 1/2″ in width for strength and long-term striking. Also, get one that is predrilled for a lanyard so that you can better grip while striking, secure the rod to your pack, and find it if you drop it (use a visible color for the lanyard).

I use a Bayite rod with great success. There are other great options out there. Make sure you get the right size and test it. Practice sparking it. As long as it produces a good, strong shower of sparks, it doesn’t matter what brand it is.

Fresnel Lens

A fresnel lens is a flat lens that concentrates light into a focused beam that can start fires. A simple, flexible, plastic lens the size of a credit card can be a failsafe fire starter, provided the sun is out. These are very cheap and easy to spread throughout your kit, so that if you become separated from your backpack, you will still have a fire starter in your wallet, boot, pocket, etc. You can buy 4-10 lenses for less than $10USD.

Tinder

You gotta have tinder to get a spark going. No this isn’t marketing for a dating app. Tinder is the fundamental micro-fuel you ignite to get a fire going. Tinder ignites into an open flame, a flame that is used to ignite kindling, which in turn is used to ignite primary fuel. Most tender you need can be found in nature for free. As always, we like to carry a backup incase the weather isn’t playing nice. A good manufactured option would be a magnesium bar. When shaved into small, thin pieces, it will ignite incredibly hot and will get a fire burning in little time. Get a Doan Magnesium Fire Starter or a bar of pure magnesium. Imitations often use less pure magnesium that can be hard to ignite.

At home you can make tinder by rubbing cotton balls in petroleum jelly. These can be stored in 35mm film canisters or other sealable plastic tube. They ignite and burn for a while, allowing you to get a fire started.

Fatwood can also be found or purchased and brought with you. When shaved into thin strips, it readily takes a spark and ignites.

Building a Fire

Here are some useful videos on fire building:

Considerations for Camp Fires

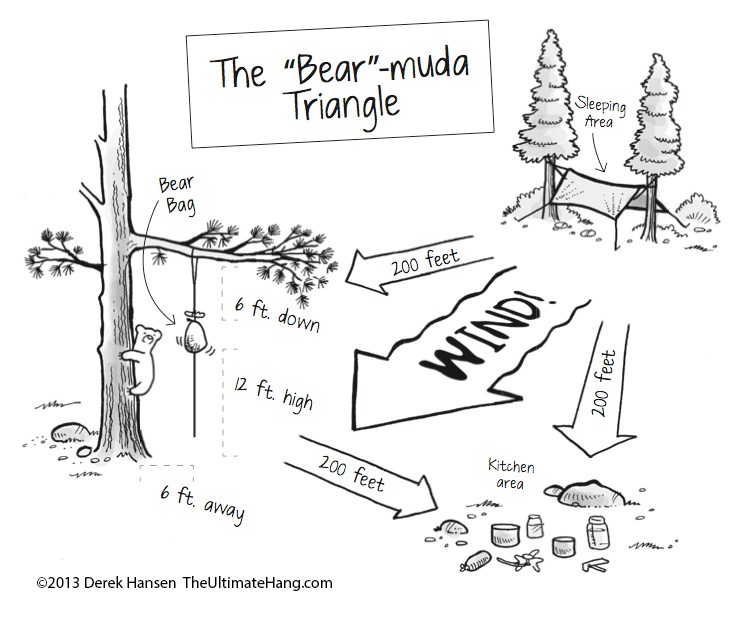

Fires are extremely useful for cooking and sanitizing as well as for keeping warm and cheerful. They also can be a dead giveaway of your presence and location. Keep fires small, limit the amount of smoke produced, and construct fire reflectors to reflect light and heat into your shelter and not into the wilderness.

The best time for stealth fires is dawn and dusk, when smoke will be obscured better than in the day and light from the fire won’t act as a beacon in the night. You can use small collapsible wood stoves to cook on that efficiently burn very little fuel and produce very little light.

Remember that smell is one of your enemies when trying to conceal your position. Cooking in the evening or at night will limit the chances of accidentally exposing passers-by to the smell of your cooking. Cooking smells are also a concern when in bear country, so keep your food stuffs away from camp and hung from a tree in a bear bag.

Food

Food for fieldcraft is a tricky thing to balance. For bugging out, you need enough calories to last you until you reach your bugout location, hopefully with comrades who have provisions or a survival camp. For a long term camp either static or nomadic, you need a consistent source of proteins, carbs, vitamins, minerals, and food preservation. This will require resupply and caching. We will examine some of the means of acquiring and storing food for long term survival and will look at short term survival foods for a bugout scenario.

Proteins

Acquiring proteins in nature is usually accomplished through hunting, trapping, or fishing. Hunting firearms have already been discussed in our Secondary Firearms article in this series. What was not discussed was hunting skills for small game (what you will want if you are one to three adults) and for large game (when you have four or more adults).

Hunting & Trapping Small Game

Small game can be broken down into birds and small mammals. The most important way to practice hunting these is to a) go to the range and shoot clays with your shotgun or rolling targets with your rimfire or bow, b) practice making traps, and b) go small game hunting.

Traps

Trapping is one of the most basic low energy ways to get food. Snares, deadfalls, and cage traps can be readily constructed, placed on game trails or near burrows, yielding occasional food with minimal effort. This should not be your primary means of capturing food, but can act as a supplemental source.

Shooting Small Game

There are some very easy exercises to practice shotgun handling for hunting. Here’s a great demonstration of these exercises:

Moving target marksmanship is extremely important for hunting small game. Shooting clays has turned into a sport unto itself, but it has tremendous value for shooting moving targets.

For rimfire hunting, rolling, self-healing targets are the way to go for live fire practice. I recommend models like the top hat, which makes movement less predictable and a ball for more predictable movement.

Of course the most important way to practice is to get out and do some hunting once your fundamental marksmanship, gun handling. and gun safety are solid. You will only learn small game behavior by spending time observing them.

Hunting Large Game

For large game, be sure to take time to understand how to take an ethical shot. A bad shot can wound an animal, leaving them wandering for days, slowly dying in pain. Only take ethical shots and always track wounded game.

Field Dressing Game

Remember, if you kill it, you eat it (so long as it isn’t diseased). Here are some helpful field dressing/butchering techniques for basic game types (Trigger Warning: Graphic):

Fishing

Fishing can provide you with very important nutrients. Active fishing can be done with a rod and reel, a spear, or with archery. Inactive fishing uses fish traps or gill nets.

Active fishing requires you to bring gear with you, or the construction of gear while in the field. The simplest way to fish is by bringing a package of hooks, a roll of line, making a fishing pole in the field and sourcing bait by finding it. Here are some examples:

Learning Indigenous skills such as fiber production, hook making, etc., will prepare you to fish with what you can gather naturally:

Here are some examples of fishing traps:

Carbs and Vitamins

Most of your carbs and vitamins will come from foraging, unless you cultivate food for long term encampments. Foraging for edibles is a highly regional pursuit. You need to spend time learning to identify edible plants, understand their nutritional/medicinal values, and understand what time of the year they will be found. This can be accomplished by reading books about wild edibles, taking survival courses in your area, and learning from elders who still have traditional knowledge of the land and plants.

I recommend the following books for my area, but local cultural and survival groups will have more regionally specific guides to check out. I use the following for where I live in southern California:

Native American Ethnobotany by Daniel E. Moerman

Probably the most important compendium of information about Indigenous plant uses in North America. I have learned about plant uses I would have never known about from this book, filling in the gaps where my elders no longer have memories. This does not teach plant identification, only traditional uses by tribe. If you live in North America, I highly advise getting a copy or requesting your library purchase a copy.

Kumeyaay Ethnobotany: Shared Heritage of the Californias by Michael Wilken-Robertson

This book is great for me because the Kumeyaay are a sister tribe to my Kwapa people. We share so many of the same traditions, plants being a big one.

California Foraging: 120 Wild and Flavorful Edibles from Evergreen Huckleberries to Wild Ginger (Regional Foraging Series) by Judith Larner Lowry

A part of a regional foraging series with good general information. Worth picking one up for your region.

The Sea Forager’s Guide to the Northern California Coast by Kirk Lombard

While this book has lots of information on seafood of the animal variety, it also has useful information about edible algaes!

Mushrooms of the Redwood Coast: A Comprehensive Guide to the Fungi of Coastal Northern California by Noah Siegel

A good guide for foraging edible mushrooms in more humid forests to the north. Mushrooms can be rewarding provided you take the time to study and practice.

You also will need to understand what kind of processing they require. Some, like acorns, require boiling to remove tannic acid. Others, like mesquite beans, require grinding to turn the pods into useable flower. Having knowledge ahead of time, without needing reference material in the field will only come with practice and developing relationships with the plants you harvest.

Minerals & Preservation

Salt. It is a vital nutrient and an effective means of preserving food. Many minerals will be naturally absorbed from the meat and plants you eat, but salt has no substitute. For shorter journeys, carrying a small 6oz container of iodized salt will serve you well. For long term encampments, you will need to buy salt in bulk and store it in caches, eventually seeking resupply through purchase or trade. Creative ways to store salt include filling a sanitized bucket with table salt / sea salt, vibrating to settle it, and add a desiccant package. You can also vacuum seal plain white, unflavored livestock salt-licks (no additives or antibiotics). you can get from a local feed store. Iodized salt though is the standard for maintaining health while cooking. You might use the bulk salt from a salt lick to make jerky for example, but use iodized salt when cooking food. Pink salt has additional minerals in it which can be a benefit for long term use.

Have a salt plan. If you can source it locally in the wilderness, you are lucky. See where your ancestors got it from (if you are Indigenous). You will need 8-9lbs of salt per person per year.

Navigation

The ability to navigate is an important skill. Today, most people navigate with their cell phone. Cell phones are problematic for fieldcraft for several reasons: they rely on spotty cell phone service, they report back your position to cell phone service providers, their triangulation can be ineffective, they require charging and may be susceptible to bad weather.

GPS is the next navigation tool most people turn to. GPS can be very useful when covering large amounts of terrain as they can store a large number of maps and satellite photos, they can leave ‘breadcrumbs’ allowing you to retrace your route, they can mark cache locations and navigate you back to their location, and they can provide you with precise coordinates for coordinating with other people.

They face a few potential downfalls to the long term operation of a GPS device. First, they need batteries, which means you will need to dedicate time to charging. This can be remedied with the mobile PowerFilm LightSaver, which can be secured to your pack and charge your device as you walk, or can be left in a sunny south facing place around camp. In cold weather, you will need to sleep with the batteries for this device to keep them from losing charge in the cold. You also will want to avoid devices that have the ability to transmit or communicate, lest you unintentionally reveal your location (such as with the Garmin GPSMAP 66i). Recommended GPS units include the Garmin GPSMAP 65s, the Garmin GPSMAP 64csx, or you can use a rugged tablet like the Samsung Galaxy Tab Active3 with a USB GPS/GLONASS dongle.

The ultimate form of navigation relies on maps and a compass. Orienteering or analog navigation has the benefit of never snitching on your location and not being subject to battery charge or satellite coverage (or availability). The basic tools you will need for this are United States Geological Survey (USGS) Quadrangle (Quad, 1:24000) or Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) 1:50000 maps for all lands you expect to cover during a bugout or an encampment, waterproof map holder, a lensatic compass, and pace counting beads (often called ranger beads).

Quadrangle maps can be purchased from the USGS, NRCan, or at local sporting goods stores, parks, or book stores usually for $8-$15USD. For $15-$17USD you can get maps from the secondary market that are printed with waterproof inks on waterproof paper. These maps are bulkier and heavier, but are extremely durable, a benefit you will have to weigh given your climates propensity for sustained precipitation. Here are some videos about understanding topographic maps:

Waterproof map holders are used for storing maps in a safe manner and for navigation using the visible portion of a folded map while it is raining. There are a wide variety of makers, so shop around, read reviews, and test it with plain paper using a fountain, hose, or shower. Once you know it is secure, you should be good to go.

Lensatic compass are rugged and reliable means of navigation. Buy a quality one and practice with it as much as you can while outdoors. Recommended versions include the Cammenga Lensatic Tritium Compass 3H (self illuminating) or the Cammenga Phosphorescent Lensatic Compass 27 (needs to be charged in sunlight during the day). Here is an introductory guide to using these compasses:

The last item you will need is a pace counter (also called ranger beads). This is useful for dead reckoning, the ability to maintain awareness of your position relative to a starting point. These can be bought, but are extremely easy to make on your own. Here are some videos about making pace beads, figuring out your pace count, and utilizing them.

It is really recommended that you learn from an experienced navigator, either a friend or in a course. This is worth the money to learn to do right. You can do it, and this will save your life. There are many other navigation skills that you will develop with practice. Always keep learning!

Conclusion

Basic survival skills require practice to cultivate. They require an inquisitive mind that is always trying new things and learning whenever possible. Nature will reward you for responsibly practicing living in communion with the land and waters. Remember to always leave your practice camps as close to as you found them, as you can. Get out there, stay safe, and good luck!

2 thoughts on “Basic Wilderness Fieldcraft: Skills For Revolutionary Survival No.9”

Comments are closed.