By Aragorn!

Published in “Green Anarchy”, Issue #19 — Spring 2005

It’s easy enough to hedge about politics. It comes naturally and most of the time the straight answer isn’t really going to satisfy the questioner, nor is it appropriate to fix our politics to this world, to what feels immovable. Politics, like experience, is a subjective way to understand the world. At best it provides a deeper vocabulary than mealy-mouthed platitudes about being good to people, at worst (and most commonly) it frames people and ideas into ideology. Ideology, as we are fully aware, is a bad thing. Why? Because it answers questions better left haunting us, because it attempts to answer permanently what is temporary at best.

It is easy to be cagey about politics but for a moment let us imagine a possibility. Not to tell one another what to do, or about an answer to every question that could arise, but to take a break from hesitation. Let us imagine what an indigenous anarchism could look like.

We should start with what we have, which is not a lot. What we have, in this world, is the memory of a past obscured by history books, of a place clear-cut, planted upon, and paved over. We share this memory with our extended family, who we quarrel with, who we care for deeply, and who often believe in those things we do not have. What we do have is not enough to shape this world, but is usually enough to get us by.

If we were to shape this world (an opportunity we would surely reject if we were offered), we would begin with a great burning. We would likely begin in the cities where with all the wooden structures of power and underbrush of institutional assumption the fire would surely burn brightly and for a very long time. It would be hard on those species that lived in these places. It would be very hard to remember what living was like without relying on deadfall and fire departments. But we would remember. That remembering wouldn’t look like a skill-share or an extension class in the methods of survival, but an awareness that no matter how skilled we personally are (or perceive ourselves to be) we need our extended family.

We will need each other to make sure that the flames, if they were to come, clear the area that we will live in together. We will need to clear it of the fuel that would end up repeating the problems we are currently having. We will need to make sure that the seeds, nutrients and soil are scattered beyond our ability to control.

Once we get beyond the flames we will have to craft a life together. We will have to recall what social behavior looks and feels like. We will have to heal.

When we begin to examine what life could be like, now that all the excuses are gone, now that all the bullies are of human size and shape, we will have to keep in mind many things. We will have to always keep in mind the matter of scale. We will have to keep in mind the memory of the first people and the people who kept the memory of matches and where and when to burn through the past confusing age. For what it is worth we will have to establish a way to live that is both indigenous, which is to say of the land that we are actually on, and anarchist, which is to say without authoritarian constraint.

First Principles

First principles are those perspectives that (adherents to) a tendency would understand as immutable. They are usually left unstated. Within anarchism these principles include direct action, mutual aid, and voluntary cooperation. These are not ideas about how we are going to transform society or about the form of anarchist organization, but an understanding about what would be innovative and qualitatively different about an anarchist social practice vis-à-vis a capitalist republic, or a totalitarian socialism.

It is worth noting a cultural history of our three basic anarchist principles as a way of understanding what an indigenous anarchist set of principles could look like. Direct action as a principle is primarily differentiated from the tradition of labor struggles, where it was used as a tactic, in that it posits that living ‘directly’ (or in an unmediated fashion) is an anarchist imperative. Put another way, the principle of direct action would be an anarchist statement of self-determination in practical aspects of life. Direct action must be understood through the lens of the events of May ’68 where a rejection of alienated life led large sections of French society into the streets and towards a radically self-organized practice.

The principle of mutual aid is a very traditional anarchist concept. Peter Kropotkin laid out a scientific analysis of animal survival and (as a corollary to Darwin’s theory of evolution) described a theory of cooperation that he felt better suited most species. As one of the fathers of anarchism (and particularly Anarcho-Communism) Kropotkin’s concept of mutual aid has been embraced by most anarchists. As a principle it is generally limited to a level of tacit anarchist support for anarchist projects.

Voluntary cooperation is the anarchist principle that informs anarchist understandings of economics, social behavior (and exclusion), and the scale of future society. It could be stated simply as the principle that we, individually, should determine what we do with our time, with whom we work, and how we work. Anarchists have wrestled with these concepts for as long as there has been a discernible anarchist practice. The spectrum of anarchist thought on the nuance of voluntary cooperation ranges from Max Stirner who refuses anything but total autonomy to Kropotkin whose theory of a world without scarcity (which is a fundamental premise of most Marxist positions) would give us greater choices about what we would do with our time. Today this principle is usually stated most clearly as the principle to freely associate (and disassociate) with one another.

This should provide us with enough information to make the simple statement that anarchist principles have been informed by science (both social and physical), a particular understanding of the individual (and their relation to larger bodies) and as a response to the alienation of modern existence and the mechanisms that social institutions use to manipulate people. Naturally we will now move onto how an indigenous perspective differs from these.

In the spirit of speaking clearly I hesitate in making the usual caveats when principles are in question. These hesitations are not because, in practice, there is any doubt as to what the nature of relationship or practice should look like. But when writing, particularly about politics, you can do yourself a great disservice by planting a flag and calling it righteous. Stating principles as the basis for a politic usually is such a flag. If I believe in a value and then articulate that value as instrumental for an appropriate practice then what is the difference between my completely subjective (or self-serving) perspective and one that I could possibly share usefully? This question should continue to haunt us.

Since we have gone this far let us speak, for a moment, about an indigenous anarchism’s first principles. Insert caveats about this being one perspective among many. Everything is alive. Alive may not be the best word for what is being talked about but we could say imbibed with spirit or filled with the Great Spirit and we would mean the same thing. We will assume that a secular audience understands life as complex, interesting, in motion, and valuable. This same secular person may not see the Great Spirit in things that they are capable of seeing life in.

The counterpoint to everything being filled with life is that there are no dead things. Nothing is an object. Anything worth directly experiencing is worth acknowledging and appreciating for its complexity, its dynamism and its intrinsic worth. When one passes from what we call life, they do not become object, they enrich the lives they touched and the earth they lie in. If everything is alive, then sociology, politics, and statistics all have to be destroyed if for no other reason but because they are anti-life disciplines.

Another first principle would be that of the ascendance of memory. Living in a world where complex artifices are built on foundations of lies leads us to believe that there is nothing but deceit and untruth. Our experience would lead us to believe nothing less. Compounding this problem is the fact that those who could tell us the truth, our teachers, our newscasters and our media devote a scarce amount of their resources to anything like honesty. It is hard to blame them. Their memory comes from the same forgetfulness that ours does.

If we were to remember we would spend a far greater amount of our time remembering. We would share our memories with those we loved, with those we visited, and those who passed by us. We will have to spend a lot of time creating new memories to properly place the recollection of a frustrated forgetful world whose gift was to destroy everything dissimilar to itself.

An indigenous anarchism is an anarchism of place. This would seem impossible in a world that has taken upon itself the task of placing us nowhere. A world that places us nowhere universally. Even where we are born, live, and die is not our home. An anarchism of place could look like living in one area for all of your life. It could look like living only in areas that are heavily wooded, that are near life-sustaining bodies of water, or in dry places. It could look like traveling through these areas. It could look like traveling every year as conditions, or desire, dictated. It could look like many things from the outside, but it would be choice dictated by the subjective experience of those living in place and not the exigency of economic or political priorities. Location is the differentiation that is crushed by the mortar of urbanization and pestle of mass culture into the paste of modern alienation.

Finally an indigenous anarchism places us as an irremovable part of an extended family. This is an extension of the idea that everything is alive and therefore we are related to it in the sense that we too are alive. It is also a statement of a clear priority. The connection between living things, which we would shorthand to calling family, is the way that we understand ourselves in the world. We are part of a family and we know ourselves through family. Leaving aside the secular language for a moment, it is impossible to understand oneself or one another outside of the spirit. It is the mystery that should remain outside of language that is what we all share together and that sharing is living.

Anarchist in spirit vs. Anarchist in word

Indigenous people in general and North American native people specifically have not taken too kindly to the term anarchist up until this point. There have been a few notable exceptions (Rob los Ricos, Zig Zag, and myself among them) but the general take is exemplified by Ward Churchill’s line “I share many anarchist values like opposition to the State but…” Which begs the question why aren’t more native people interested in anarchism?

The most obvious answer to this question is that anarchism is part of a European tradition so far outside of the mainstream that it isn’t generally interesting (or accessible) to non-westerners. This is largely true but is only part of the answer. Another part of an answer can be seen in the surprisingly large percentage of anarchists who hold that race doesn’t matter; that it is, at best, a tool used to divide us (by the Man) and at worst something that will devolve society into tribalism [sic]. Outside of whether there are any merits to these arguments (which I believe stand by themselves) is the violation of two principles that have not been discussed in detail up until this point — self-determination and radical decentralization.

Self-determination should be read as the desire for people who are self-organized (whether by tradition, individual choice, or inclination) to decide how they want to live with each other. This may seem like common sense, and it is, but it is also consistently violated by people who believe that their value system supersedes that of those around them. The question that anarchists of all stripes have to answer for themselves is whether they are capable of dealing with the consequences of other people living in ways they find reprehensible.

Radical decentralization is a probable outcome to most anarchist positions. There are very few anarchists (outside of Parecon) that believe that an anarchist society will have singular answers to politics, economy, or culture. More than a consequence, the principle of radical decentralization means it is preferable for there to be no center.

If anarchists are not able to apply the principles of self-determination to the fact that real living and breathing people do identify within racial and cultural categories and that this identification has consequences in terms of dealing with one another can we be shocked that native people (or so-called people of color) lack any interest in cohabitating? Furthermore if anarchists are unable to see that the consequence of their own politic includes the creation of social norms and cultures that they would not feel comfortable in, in a truly decentralized social environment, what hope do they have to deal with the people with whom they don’t feel comfortable today?

The answer is that these anarchists do not expect to deal with anyone outside of their understanding of reality. They expect reality to conform to their subjective understanding of it.

This problem extends to the third reason that native people lack interest in anarchism. Like most political tendencies anarchism has come up with a distinct language, cadence, and set of priorities. The tradition of these distinctions is what continues to bridge the gap between many of the anarchist factions that have very little else in common. This tradition is not a recruiting tradition. There is only a small evangelical tradition within anarchism. It is largely an inscrutable tradition outside of itself.

This isn’t a problem outside of itself. The problem is that it is coupled with the arrogance of the educated along with the worst of radical politics’ excesses. This is best seen in the distinction that continues to be made of a discrete tradition of anarchism from actions that are anarchistic. Anarchists would like to have it both ways. They would like to see their tradition as being both a growing and vital one along with being uncompromising and deeply radical. Since an anarchist society would be such a break from what we experience in this world, it would be truly different. It is impossible to perceive any scenario that leads from here to there. There is no path.

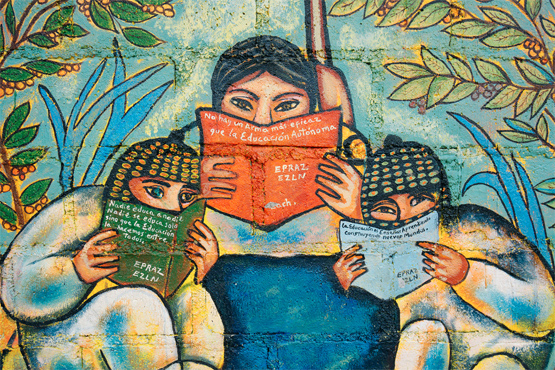

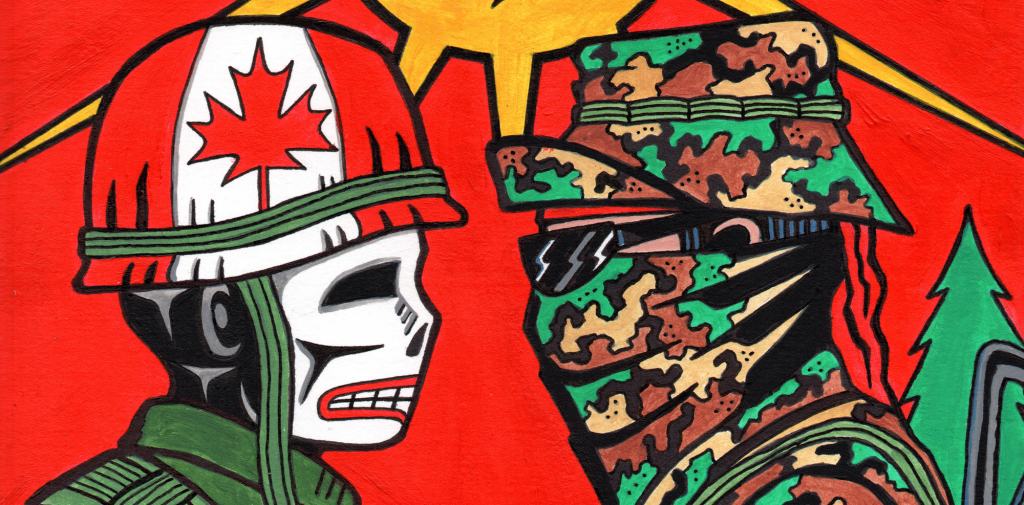

The anarchist analysis of the Zapatistas is a case in point. Anarchists have understood that it was an indigenous struggle, that it was armed and decentralized but habitually temper their enthusiasm with warnings about a) valorizing Subcommandante Marcos, b) the differences between social democracy and anarchism, c) the problems with negotiating with the State for reforms, etc. etc.

These points are valid and criticism is not particularly the problem. What is the problem is that anarchist criticism is generally more repetitive than it is inspired or influential. Repetitive criticisms are useful in getting every member of a political tendency on the same page. Criticism helps us understand the difference between illusion and reality. But the form that anarchist criticism has taken about events in the world is more useful in shaping an understanding of what real anarchists believe than what the world is.

As long as the arbiters of anarchism continue to be the wielders of the Most Appropriate Critique, then anarchism will continue to be an isolated sect far removed from any particularly anarchistic events that happen in the world. This will continue to make the tendency irrelevant for those people who are interested in participating in anarchistic events.

Native People are not gone

For many readers these ideas may seem worth pursuit. An indigenous anarchism may state a position felt but not articulated about how to live with one another, how to live in the world and about the decomposition. These readers will recognize themselves in indigeneity and ponder the next step. A radical position must embed an action plan, right?

No, it does not.

This causality, this linear vision of the progress of human events from idea to articulation to strategy to victory is but one way to understand the story of how we got from there to here. Progress is but one mythology. Another is that the will to power, or the spirit of resistance, or the movement of the masses transforms society. They may, and I appreciate those stories, but I will not finish this story with a happy ending that will not come true. This is but a sharing. This is a dream I have had for some time and haven’t shown to any of you before, which is not to say that I do not have a purpose…

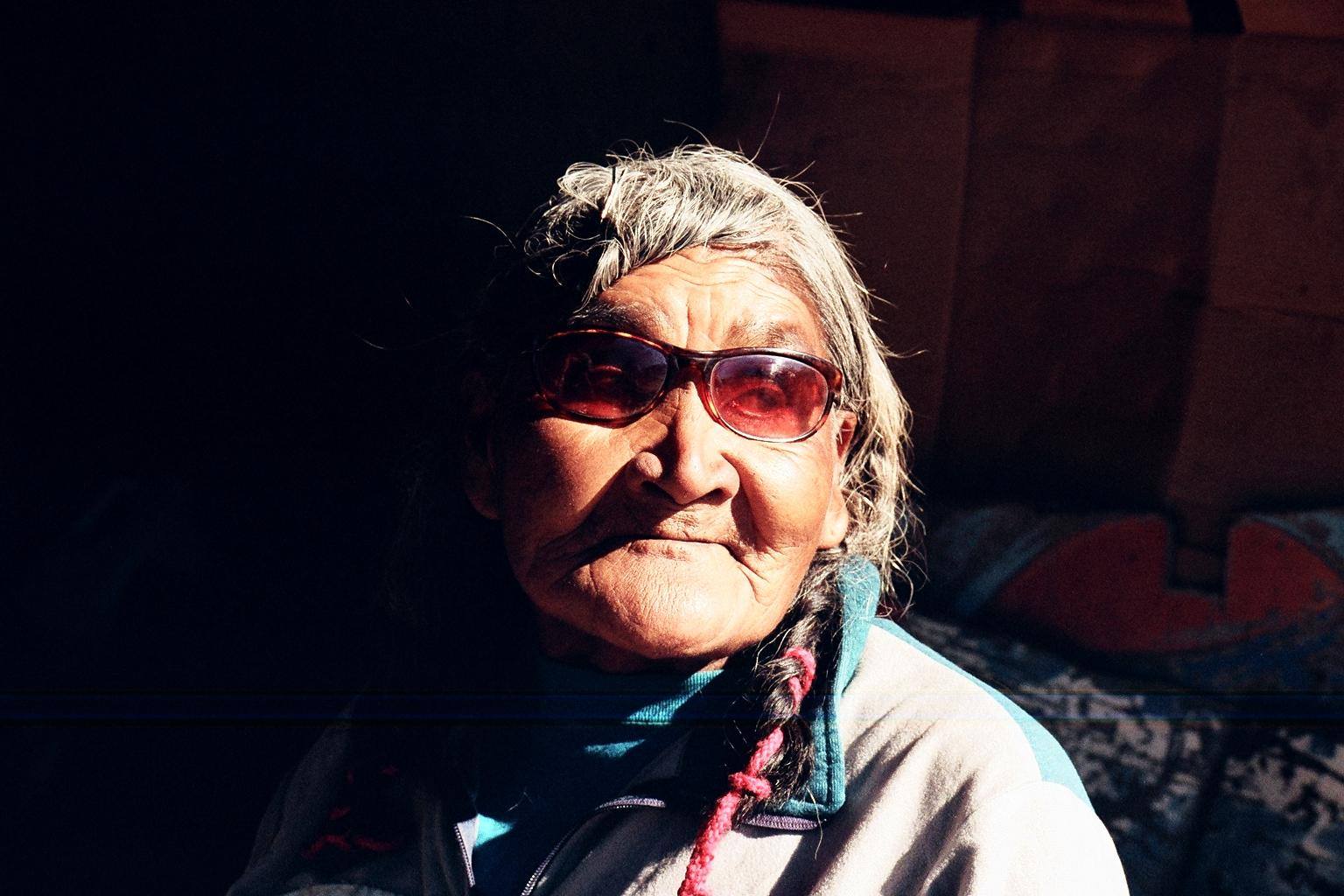

Whether stated in the same language or not, the only indigenous anarchists that I have met (with one or three possible exceptions) have been native people. This is not because living with these principles is impossible for non-native people but because there are very few teachers and even fewer students. If learning how to live with these values is worth anything it is worth making the compromises necessary to learn how people have been living with them for thousands of years.

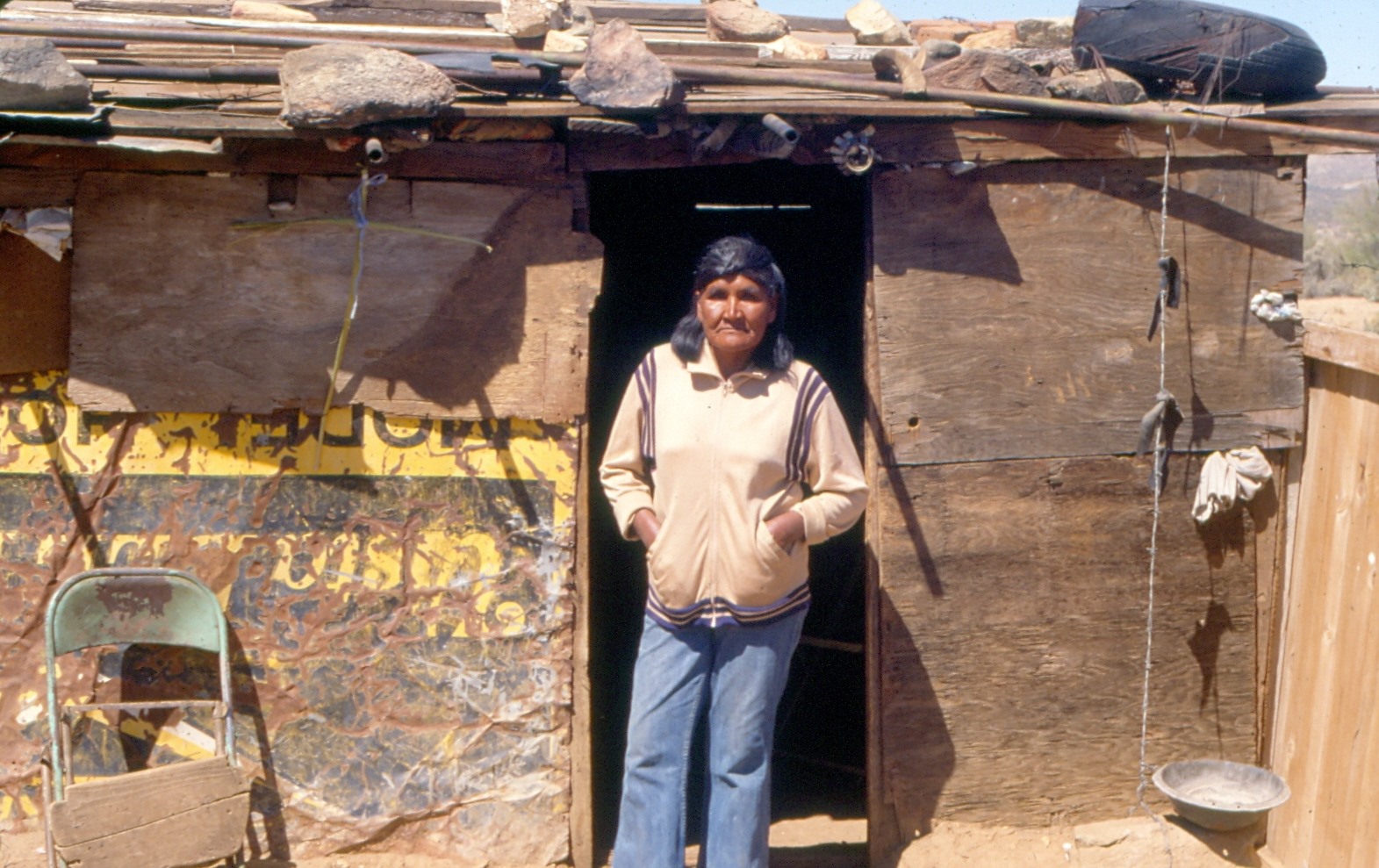

Contrary to popular belief, the last hope for native values or an indigenous world-view is not the good hearted people of civilized society. It is not more casinos or a more liberal Bureau of Indian Affairs. It is not the election of Russell Means to the presidency of the Oglala Sioux Tribe. It is patience. As I was told time and time again as a child “The reason that I sit here and drink is because I am waiting for the white man to finish his business. And when he is done we will return.”